Counties: The Missing Pieces in the Broadband Puzzle

Monday, June 14, 2021

Digital Beat

Counties: The Missing Pieces in the Broadband Puzzle

In January 2021, we launched the Virginia County Broadband Survey to better understand what counties across the Commonwealth of Virginia are doing to close the digital divide in their communities, and how broadband factors into their policy plans for the year. Almost by definition, counties in Virginia are rural, since, in the Commonwealth, cities are independent and separate political entities from the counties that surround them. With this in mind, our research focused solely on the 95 counties within the Commonwealth of Virginia. We initially sent the survey to county administrators, and, failing a return, sent it to information technology directors, economic directors, and/or county broadband authorities. Presently, 42 of Virginia’s 95 counties have responded, giving us a response rate of 44%. The goal is to secure a 100% return rate, and, ultimately, create a publicly searchable database of county broadband plans in Virginia.

Virginia County Broadband Survey

The inspiration for this research is found in the ongoing recognition by policymakers and researchers about the role of states and communities in broadband planning, funding, and deployment. As the interface between states and municipalities, we hypothesize that counties play, and will continue to play, an increasingly crucial role in broadband deployment.

Questions on the Virginia County Broadband Survey included asking where broadband falls on the county’s list of policy priorities if the county had allocated public funds to broadband initiatives in the last two years, and if the county allocated CARES Act funding to broadband initiatives. We also asked counties to identify key challenges to broadband deployment.

In this article, we offer preliminary analysis of a question about broadband deployment. We asked counties to self-report broadband coverage levels at 25/3 Mbps, 50/10 Mbps, and 100/20 Mbps (respectively). The results were troubling, if unsurprising: massive inconsistencies between self-reported broadband deployment and the data provided by the Federal Communications Commissions.

Bad data leads to bad decisions

When considering public investment in broadband deployment, bad data leads to bad decisions. This is, of course, a belabored point among broadband policy researchers, advocates, scholars, and lawmakers. Nevertheless, the issues of mapping and bad deployment data are crucial to understand and to solve, especially as the country looks towards greater levels of public spending on broadband. The Federal Communications Commission’s broadband data paints the picture of a connected America: 96.5% of Americans have access to broadband speeds at or above 25 Mbps download/3 Mbps upload, including 82.7% of rural Americans and 79.1% of residents on Tribal lands. Independent studies have demonstrated, however, that the FCC’s data overestimates the level of connectivity in the United States by upwards of 50%.

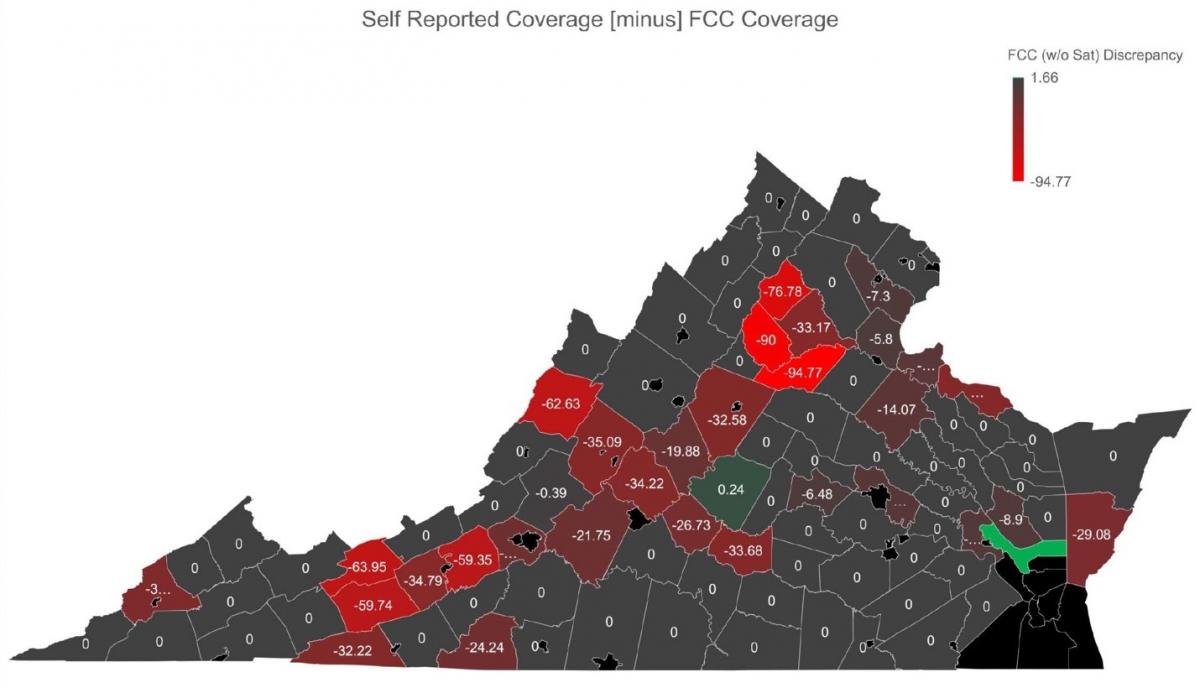

Preliminary data from our survey joins those studies that demonstrate the failure of the FCC’s broadband data. We found significant discrepancies when comparing the FCC’s estimated levels of connectivity amongst Virginia counties and the counties’ self-reported levels. Over 90% of the counties that responded to our survey were severely overcounted, one was undercounted, and two fell within rounding distance. Counties that were overcounted outnumber those approximately equal and undercounted by the FCC by a factor of 10:1. The only county that was undercounted by the FCC was the generally-more-urban York County; it reported 100% coverage at speeds of at least 25/3 (whereas the FCC reports coverage of 98.34%). Given the small discrepancy, this could also be due to a rounding error. Two more counties—Buckingham and Botetourt—self-reported within a 0.5% range of the FCC’s data – enough to be negated by simple rounding. That leaves the other thirty-six counties where the discrepancies ranged from a 5.8% in Stafford County to an astonishing 94.77% discrepancy in Orange County. Joining Orange, Madison county reported a discrepancy of 90%, with the county reporting 10% coverage, while the FCC reported 100% coverage by three providers. Including every county that responded to our survey, the average FCC vs self-reported coverage discrepancy was 31.18% across the commonwealth.

The data presented in this post represent the assessments of county-level officials, thus offering another layer on the broadband data cake that already includes data from the FCC, independent third parties (like LightBox and Geo Partners), and crowdsourced data. We operated on the premise that local officials know their communities better than anyone else: the best data, we argue, therefore, is local data. The data collected in this survey is consistent with county-level data reported by USTelecom, where discrepancies were found in almost 53% of census blocks in Virginia. Moreover, USTelecom found that 39% of rural locations in Virginia that were deemed served by the FCC were in fact unserved. Our findings also loosely track the broadband data usage figures recently released by Microsoft. To use but one example, the FCC says that Albemarle County (the county in which the University of Virginia is located) is 92.58% served at 25/3. Albemarle reported that it is 60% served. Figures released by Microsoft support our data as 51% of residents in Albemarle County have a device that received a Microsoft update. As we work to further analyze our data, including the self-reported county deployment figures, we endeavor to verify the deployment responses using third-party data.

Broadband data discrepancies lead to a host of problems for counties. Communities may find it hard to attract new broadband providers in areas where it is presumed that competing networks already exist as companies are hesitant to make the large capital investment needed to build new networks. Perhaps the worst problem is the impact data discrepancies have on funding. Unconnected counties can be deprioritized or even disqualified from state and federal broadband funding programs if they are considered “served” by the FCC. Bad data already impacted Phase I of the FCC’s Rural Digital Opportunity Fund (RDOF) reverse auction.

The FCC has recently taken first steps in correcting and improving its broadband deployment data gathering methodologies. This includes a broadband data task force with a mandate to improve data collection and a portal by which consumers can self-report their broadband experiences. As the FCC and Acting Chair Jessica Rosenworcel work to improve the Commission’s broadband deployment data-gathering methodologies, counties and county assessments must factor into design and conversation.

At least in the state of Virginia, counties are rural, yet they have been left out of the design of broadband deployment, and the conversation of rural broadband. Nevertheless, they are a crucial part of the local broadband story, and their support can go a long way in bridging the digital divide. In Virginia, for instance, dozens of counties have applied for state grants in partnerships with private providers. During the pandemic, Louisa County funded solar-powered hotspots, while Nelson County used CARES Act funding to expand the fiber-to-the-home footprint of the Central Virginia Electric Cooperative’s (CVEC) Firefly ISP.

County officials know their areas, their residents, and their community needs. Each county is a separate piece that completes the picture of broadband in Virginia; the puzzle of universal broadband access won’t be completed until every county has 100% access.

There are three major takeaways from this early analysis of data from the Virginia County Broadband Survey:

- While states and municipalities have been highlighting as key stakeholders in broadband planning and deployment, the role of counties has, until now, been underappreciated by policymakers and broadband researchers.

- The FCC’s data continue to fail in terms of delivering a trustworthy and accurate representation of broadband deployment in the United States.

- County officials know their communities – we need to trust them and bring them to the table when discussing broadband deployment plans at both the state and local levels.

As we receive new responses to our survey, we will continue to report our findings.

If any counties in Virginia have not yet responded to our invitation to take the survey, they should feel free to contact us at: cali@virignia.edu

Christopher Ali, PhD is an Associate Professor of Media Studies at the University of Virginia and former Faculty Fellow at the Benton Institute for Broadband & Society. He is the author of the forthcoming book Farm Fresh Broadband: The Politics of Rural Connectivity to be released in September 2021 from MIT Press.

Abby Simmerman is a graduate student in Media, Culture, and Technology at the University of Virginia. She studies the equitability of broadband and media technology.

Nicholas Lansing is an undergraduate student in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Virginia. A native of southwestern Ohio, Nicholas is majoring in Foreign Affairs and Latin American Studies.

The Benton Institute for Broadband & Society is a non-profit organization dedicated to ensuring that all people in the U.S. have access to competitive, High-Performance Broadband regardless of where they live or who they are. We believe communication policy - rooted in the values of access, equity, and diversity - has the power to deliver new opportunities and strengthen communities.

© Benton Institute for Broadband & Society 2021. Redistribution of this email publication - both internally and externally - is encouraged if it includes this copyright statement.

For subscribe/unsubscribe info, please email headlinesATbentonDOTorg