From Midterms to What?

Tuesday, November 13, 2018

Digital Beat

From Midterms to What?

Instant analysis is most often the unhappy victim of subsequent events, but it has become the sport of the day, and few of us can resist its temptation. I am no exception, so herewith some initial thoughts on the elections just completed. Feel free to burn these musings so I’m not held accountable for them as the future unfolds. The midterms just completed (except for recounts) were historically important, and in this critical time for our democracy, we must try to make some sense of where we are. So here goes.

The bad news is split government; the good news is split government. Taking the latter first, leaving unchecked the current Administration’s control of both the Executive and Legislative branches could only have encouraged its bull-in-the-china-shop rampage against its arch-enemy—the “administrative state.” Its many successes in dismantling public interest government in less than two years, poisonous as this has been, would only have been prologue to an even more ambitious onslaught over the next two years. The outcome of the recent elections can, with a lot of skill and a little luck, slow the demolition.

Split government is far from ideal government, to be sure, but its function for the upcoming two years is, first, to put the brakes on the Trump devastation and, secondly but equally important, tee up some real issues for citizens to deliberate as we move toward 2020.

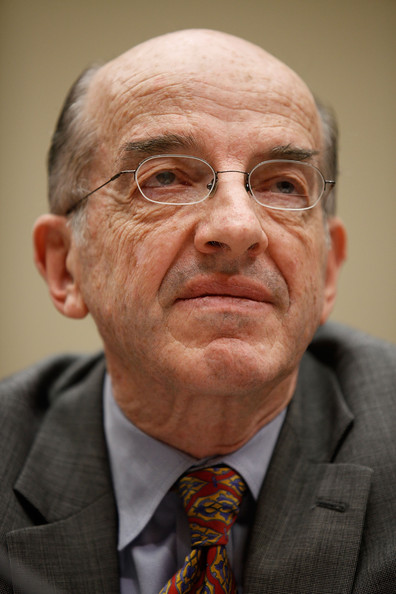

My focus is communications policy and its formative impact on the underpinnings of our democracy. I served as a minority member of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) for most of my nearly 11 years there. We were a “split” 3-2 commission by statute, and the party in power—not mine—was more often than not in control. While many of our decisions were non-contentious, non-partisan, and unanimous, some of the big issues like broadband build-out, an open internet, and industry consolidation broke down along more partisan lines. So I knew going in that I was not about to get a lot of my views on these issues translated into public interest rules and regulations.

Learn more about Michael Copps's FCC tenure in The Media Democracy Agenda: The Strategy and Legacy of FCC Commissioner Michael J. Copps

For me, the challenge was to help prevent more bad policies from prevailing. The agency was approving telecommunications and media mergers by the basketful, writing an end to competition, tell-it-like-it-is journalism, and consumer protection. It was late to the game in getting broadband deployed to every corner of the land, leaving us far behind other countries because our agency was in thrall to the misguided idea that government had no role to play in the process. And it was hostile to the idea of net neutrality, which is absolutely essential for an open internet. I knew the FCC majority wasn’t about to help me on these critically important issues, but I believed that a majority of the American people, once apprised of the high stakes involved, would help slow down decisions that were often the brainchildren of the giant media and telecom companies. That’s why Commissioner Jonathan Adelstein and I went on the road all across America holding town hall meetings to let citizens understand what was going on at the FCC. We couldn’t stop the special interest train—but we helped, at least to some extent, slow it down until a brighter day came. That day came after 2008, but unfortunately, it didn’t last. Now it’s history.

I expect that the new majority in the House of Representatives, while it will work for good legislative outcomes, will find it very difficult to convince both the Senate and the President to go along. In the give-and-take of the legislative process, perhaps some of these initiatives can see the light of day. I certainly hope so. Perhaps an infrastructure bill including aggressive broadband build-out could be cobbled together, but so far it’s been talk rather than action. Greater scrutiny over pending mergers such as T-Mobile-Sprint would also be welcome. Yet I fail to see a meaningful Congressional slow-down of media consolidation, for example, in the immediate future. I don’t see comprehensive action to address the many challenges of the internet. After all these years, Washington continues to squabble over something as basic as net neutrality protections, not even discussing the internet challenges beyond that—things like the spiraling commercialization of the 'Net, its seeming immunity from public interest oversight, and the lack of a model to incent serious journalism online. Every day we pay the price of the old adage that “bad news drives good news” out of circulation. These are challenging questions where the public looks to its elected leaders for answers.

The new House of Representatives, even if it cannot expect to resolve all these challenges, can at least push them front-and-center for the American people. It can hold hearings (hopefully a lot of them outside the Beltway), conduct workshops, produce studies, mobilize the grassroots, and put forth proposals that could change the quality of our public dialogue and help usher in public interest governance next time around the electoral track. The new House can also introduce new voices into the discussion that have largely fallen on deaf ears the past two years. This includes people of color and other marginalized communities such as the elderly, disabled, low-income, Native Americans, LGBT, and veterans. These communities, many of whom live outside Washington, DC, offer unique perspectives on communications policies and must be part of the conversation.

As an FCC commissioner, I saw first-hand that when these issues were discussed at hearings and town hall meetings and other forums, they elicited both understanding and support. More than that, they revealed that most people already favored action to guarantee net neutrality and to bring broadband to places where the private sector has no interest in deploying it (read rural America, Native America, and inner cities). People just were at a loss as to how to go about making good things happen in the political climate that surrounded us. But then they got involved, they organized, they wrote to the FCC, they petitioned Congress, and their concerns became issues of public moment. The FCC eventually came around to enacting good net neutrality rules under Chairman Tom Wheeler in 2015, and it applied at least some brakes on media industry consolidation (not enough, unfortunately), and it passed meaningful rules to protect consumer online privacy. Then the Trump administration came to town, and acting with its big industry and Congressional allies, reversed almost all of this, and then put its wrecking ball to work demolishing public interest media and telecom protections that had been on the books for generations.

The 2018 midterms further enhanced my belief that voters are of a mind to support policies that advance the common good. A headline in the November 8 Washington Post summed it up: “Progressive ballot measures win over even red-state voters.” The article cited successful state ballot measures on everything from health policy to minimum wages, Congressional redistricting, electoral reforms, etc., etc. And it trenchantly noted that these successes “highlight the approach advocates took in trying to get the ballot measures passed—namely, by not associating them with either party.” To that, I say “Amen!” because I have seen, everywhere I go to talk about media and telecom challenges, Republicans, Democrats, and Independents who are overwhelmingly supportive. Again, I’m talking beyond the Beltway, at the grassroots. Inside that fabled road, the power of the special interests, with their bundles of money, holds sway. It’s telling that the political ad money spent this year broke all previous midterm campaign records. Anyone who’s been watching TV knew that already.

So as we prepare for a new Congress coming in January, let’s begin by recognizing there are lots of new Members who need to be brought up to speed on communications issues. New Members from either party will be courted by an army of industry lobbyists who are, at this very moment, plotting on how to ingratiate themselves with the new arrivals. Advocates of reform cannot assume that a new House of Representatives means that new Members are automatically on board with a public interest agenda. We must engage with these folks on the democratic principles of open and accessible media. We should also urge Congressional leaders to fashion an agenda that focuses on oversight and reform, not from the standpoint of trying to cure every ill in the next two years of divided government, but instead focusing on bringing the country along on issues that our diminished media isn’t able, or doesn’t want, to adequately cover. Media consolidation and open internet issues deserve more than an occasional mention in the business section—and I include in this observation even some of our leading newspapers. On TV and cable, these issues are virtual no-shows.

Misguided government media policies over the past generation have devastated the news and information upon which democracy depends. Industry didn’t cause this hemorrhage by itself—it took the willing accomplice of special interest government. Successful self-government rests upon an electorate that can count on real news and deep-dive journalism. Traditional media has lost most such journalism, and online media has yet to discover a model to support it.

The midterm results give us an opportunity to slow the unthinking destruction of the last two years and to reinvigorate our national conversation with the kind of dialogue that befits our challenged country. There is no guarantee this will happen, of course. Success will depend upon smart strategy, public outreach, and grassroots mobilization. It’s difficult work, but it’s our work. The bottom line is that all the great reforms in our nation’s history have come, not as a gift from Washington, DC, but from a citizenry informed and organized and insistent upon making things right. We have a little better chance to do this now than we did a week ago.

Michael Copps served as a commissioner on the Federal Communications Commission from May 2001 to December 2011 and was the FCC's Acting Chairman from January to June 2009. His years at the Commission have been highlighted by his strong defense of "the public interest"; outreach to what he calls "non-traditional stakeholders" in the decisions of the FCC, particularly minorities, Native Americans and the various disabilities communities; and actions to stem the tide of what he regards as excessive consolidation in the nation's media and telecommunications industries. In 2012, former Commissioner Copps joined Common Cause to lead its Media and Democracy Reform Initiative. Common Cause is a nonpartisan, nonprofit advocacy organization founded in 1970 by John Gardner as a vehicle for citizens to make their voices heard in the political process and to hold their elected leaders accountable to the public interest.

Benton, a non-profit, operating foundation, believes that communication policy - rooted in the values of access, equity, and diversity - has the power to deliver new opportunities and strengthen communities to bridge our divides. Our goal is to bring open, affordable, high-capacity broadband to all people in the U.S. to ensure a thriving democracy.

© Benton Foundation 2018. Redistribution of this email publication - both internally and externally - is encouraged if it includes this copyright statement.

For subscribe/unsubscribe info, please email headlinesATbentonDOTorg