Against Digital Redlining: Lessons from Philadelphia’s Digital Connectivity Efforts during the Pandemic

Wednesday, August 24, 2022

Digital Beat

Against Digital Redlining:

Lessons from Philadelphia’s Digital Connectivity Efforts during the Pandemic

Internet service providers’ discriminatory underinvestment in broadband infrastructure and services—referred to as “digital redlining” for disproportionately affecting low-income communities of color—is drawing increased public scrutiny, including from policymakers. The Federal Communications Commission recently initiated an inquiry, mandated by Congress, into eliminating such digital discrimination, defined as the failure to provide or maintain broadband service or the provision of inferior service, including in terms of affordability and speed. While major service providers like AT&T have disputed the existence of digital redlining, clear evidence of underinvestment and lack of quality service options in low-income Black communities in major cities suggests otherwise. Our recent study of Philadelphia’s public and private connectivity efforts during the pandemic sheds light on key political economic relationships underpinning digital redlining and persistent challenges to overcoming them.

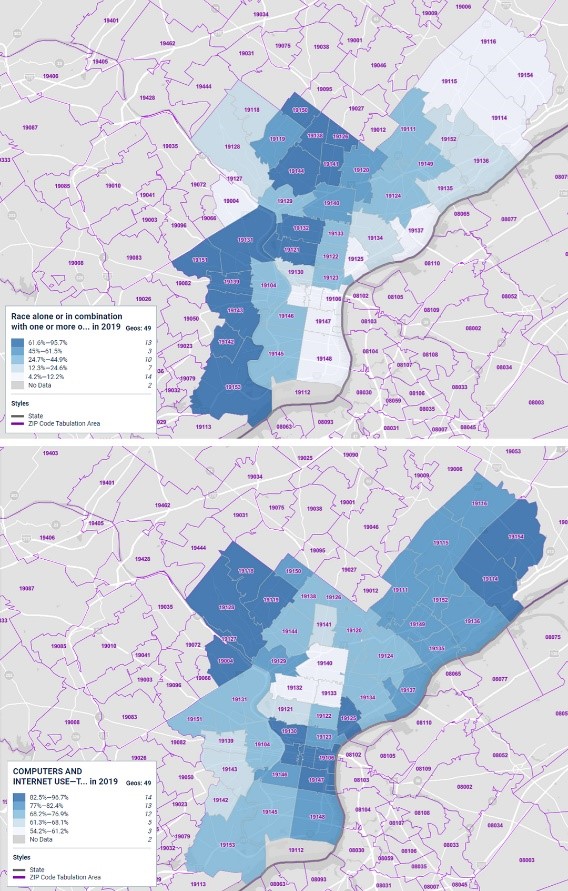

As one of the largest and least connected urban centers in the country, with a history of redlining whose legacy continues to marginalize its Black communities, Philadelphia is an instructive case study for digital inclusion. Though it’s 100% connected according to FCC data, American Community Survey (ACS) census data reveals a stark digital divide that falls largely along racial and socioeconomic lines, driven partly by service costs that are unaffordable for impoverished communities. Striking digital divides afflict most of the city’s Black communities as reflected in the figure below, illustrating broadband adoption rates and self-reported racial identity patterns according to 2019 ACS data. For example, only 54% of the residents of the city’s historically Black Allegheny West neighborhood (19132 zip code) report having home broadband services. Moreover, data collected by the nonprofit MLab indicates average download speeds in the neighborhood are only 16 Mbps, falling below the current FCC definition of broadband. Similar patterns exist in other majority Black neighborhoods (e.g., Haddington, 19139 zip code, and Elmwood, 19142 zip code). Conversely, broadband adoption in majority white communities, like the wealthy Fairmount and Bella Vista neighborhoods (19130 and 19147 zip codes, respectively), is significantly higher (and service is faster). Exceptions exist in low-income majority white neighborhoods like Port Richmond (19134 zip code), reflecting the intersection of lower broadband adoption rates with lower household income and lower education in addition to race. However, the city’s significant poverty levels disproportionately afflict its Black communities, and these neighborhoods bear the brunt of its digital inequalities.

reported Philadelphia broadband subscriptions by zip code (Data source: ACS 2019).

In addition to being the headquarters of Comcast, the nation’s largest broadband provider, Philadelphia was also one of the country’s early experimenters with municipal broadband. In 2004, the city launched the “Wireless Philadelphia” project to construct the largest municipal Wi-Fi grid in the U.S. especially designed to connect low-income residents. However, when Earthlink, the company that won the bid to build and run the network, pulled out of the project, “Wireless Philadelphia” collapsed. The initiative’s failure served as convenient ammunition for private providers like Verizon to lobby the Pennsylvania state legislature to eventually pass HB30. This law significantly restricts municipal broadband projects in the state by preventing municipalities from providing broadband if the community is already served by a private provider or if one agrees to build infrastructure in an unserved area after being requested to do so. Similar legal barriers exist in 18 other states, ensuring that public broadband options remain off the table for many communities.

Like most other U.S. cities without a municipal network, Philadelphia’s broadband offerings come from private providers. According to 2019 FCC data, Philadelphia had total broadband coverage heading into the pandemic that was provided by five companies offering satellite, cable, and fiber Internet in various parts of the city. For fixed wireline high-speed broadband services however, most residents had to choose between an effective duopoly of either Comcast or Verizon. In U.S. cities, such duopolies are the rule, not the exception.

As our case study illustrates, broadband provision in a concentrated, private provider market had stark consequences during the pandemic. This was especially true given that high quality connections became essential for everything from getting medical aid and ordering groceries to participating in school and work. Existing patterns of exclusion, largely unaddressed by private providers, had left cities like Philadelphia ill-prepared to rapidly shift to remote activity to protect their residents, especially in the poorest communities. Meanwhile, the communities most impacted by digital redlining also disproportionately bore the brunt of the economic crisis brought on by the pandemic, making quality broadband connections even further beyond reach at the precise moment they became increasingly essential.

Drawing on news accounts, policy documents, and interviews with city staff, our case study finds that Philadelphia’s pandemic digital inclusion efforts faced challenging logistics, limited data on the unconnected, funding concerns, and pushback from providers. Pandemic inclusion efforts by the municipal government, the school district, community anchor organizations, and private providers like Comcast prioritized access and cost over broadband speeds—thereby creating a secondary divide by preventing low-cost plan subscribers from getting sufficiently fast service for basic pandemic-related activities.

With a lack of private and public broadband options in the city, our interviewees stated that Comcast was an essential partner in the municipal government’s connectivity strategy. Yet private-sector, low-income internet plans like Comcast’s Internet Essentials—pitched as a key connectivity intervention long before the pandemic—were too slow to support pandemic-era necessities, like remote learning. Instead, such interventions initially intensified patterns of exclusion in communities of color. For example, residents of the city’s under-connected and poorer neighborhoods, such as West Philadelphia, had to navigate complicated sign-up processes only to find themselves denied due to an outstanding debt on their account. Our interviewees noted that such issues were eventually resolved, but Comcast did not increase the internet speeds of these low-cost plans to support a range of pandemic-related broadband needs such as remote education until a year into the crisis after significant pressure from local activist groups.

Absent public alternatives to the private broadband provider duopoly, the municipal government deployed a range of interventions to expand and improve connectivity for its most marginalized residents, including distributing mobile Wi-Fi devices for the homeless and housing insecure. In our interviews, city officials noted that subsidies proved to be the most effective: a 2021 City of Philadelphia survey found a near 15% increase in households with high-speed Internet access, with more than half owing to free or discounted connectivity programs. Yet, the efforts were overall insufficient given the scope of the city’s pronounced digital divide going into the pandemic, with one-third of Philadelphia’s households, particularly in the city’s Black communities that were experiencing “subscription vulnerability.” In addition to lacking the necessary devices and digital skills, households in these communities often were unable to afford connections without ongoing discount or subsidy. Such deficits reflect a troubling legacy of broadband policy deferring to private provision with limited competition and therefore little incentive to reduce prices.

Philadelphia’s fraught and uneven pandemic connectivity efforts represent the costs of relying on concentrated internet service markets for broadband provision. The pandemic not only highlighted the public good nature of reliable internet access, but also served as a stark demonstration of which publics are excluded from this essential infrastructure due to high service costs or whose access is inferior in terms of qualities like speed. Such digital redlining follows a market logic: private providers have lower rates of return from Black communities because of high rates of poverty (resulting from historically discriminatory socioeconomic marginalization) and therefore are less willing to invest in quality infrastructure. Laws banning public alternatives to private provision in cities like Philadelphia intensify these dependencies on the private sector, impacting their most marginalized residents, especially during public emergencies. In fact, early assessments suggest that cities with municipal networks like Chattanooga were effective at connecting marginalized residents during the pandemic. Admittedly, many of these cities are smaller than Philadelphia. However, according to one study of the similar-sized Canadian city of Calgary, a robust municipal broadband and generous federal subsidies played a key role in the city’s pandemic-era connectivity efforts.

Philadelphia’s experience most likely reflects pandemic connectivity struggles in other major U.S. urban areas. Assessing how cities strategized to provide quality broadband services during a profound public emergency, particularly for their most marginalized residents, should be a priority for policymakers and for researchers studying digital inequities. Such studies can help identify best practices, demystify the structural impediments to equitable digital inclusion, and guide policy interventions toward providing broadband services that all members of any democratic society deserve.

Pawel Popiel is the George Gerbner Postdoctoral Fellow at the Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania. His research focuses on information and technology policy, particularly how politics shapes the regulation of digital media and emergent technologies.

Victor Pickard is the C. Edwin Baker Professor of Media Policy and Political Economy at the University of Pennsylvania’s Annenberg School for Communication, where he co-directs the Media, Inequality & Change (MIC) Center. He has authored or edited six books, including America’s Battle for Media Democracy and Democracy Without Journalism? Confronting the Misinformation Society.

The Benton Institute for Broadband & Society is a non-profit organization dedicated to ensuring that all people in the U.S. have access to competitive, High-Performance Broadband regardless of where they live or who they are. We believe communication policy - rooted in the values of access, equity, and diversity - has the power to deliver new opportunities and strengthen communities.

© Benton Institute for Broadband & Society 2022. Redistribution of this email publication - both internally and externally - is encouraged if it includes this copyright statement.

For subscribe/unsubscribe info, please email headlinesATbentonDOTorg